Introduction

Last session we learned how browsers work, what HTTP and HTML are and how to use curl and wget to imitate a browser.

Today we'll dive deeper into the inner workings of browsers.

Specifically, we will:

- learn how to use the developer tools to inspect the requests it makes

- learn what cookies are

- learn how to use them from the command line

- learn how to write Python scripts that send HTTP requests

Reminders and Prerequisites

Remember these concepts from the previous session:

- by default, HTTP is a stateless protocol. Every request is independent from any other

- HTTP supports fixed methods, such as

GET,PUT,POSTetc. - HTTP servers respond with status codes and, optionally, data.

- web browsers such as Firefox are HTTP clients

curlandwgetare used to send HTTP requests and to download files, respectively

For this session, you need:

- a working internet connection

- basic knowledge of the HTTP protocol

- a Linux machine

- a Firefox browser

- a Python interpreter (at least Python3.6)

Sending HTTP Requests from Python

The module we need in order to handle requests in Python is called requests.

It contains methods for all types of HTTP requests: GET, POST, etc.

import requests as req

URL = 'https://httpbin.org'

# Send a `GET` request.

# `params` is a dictionary of query parameters.

# `response` is an object.

response = req.get(f'{URL}/get', params={'name': 'SSS', 'role': 'boss'})

# This request is equivalent to:

# GET URL?name=SSS?role=boss

# We must access its fields to gain specific information.

print(response.status_code) # The status code returned by the server

print(response.text) # The HTML sent by the server

payload = {'skill': 'infinite'}

response = req.post(f'{URL}/post', data=payload)

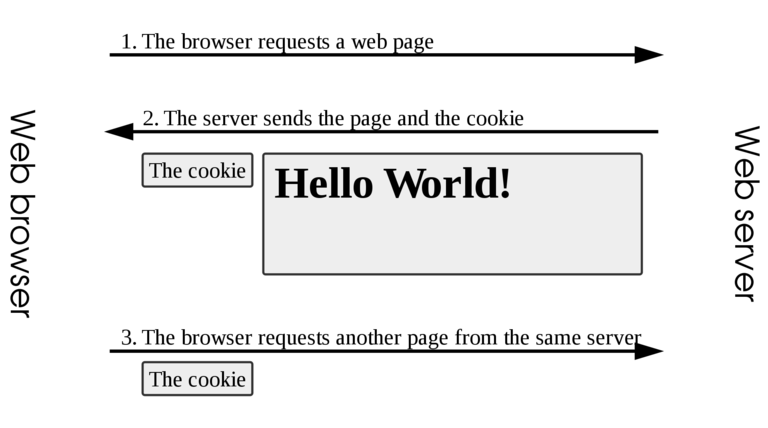

Cookies

HTTP is a stateless protocol used to communicate over the internet. This means that a request is not aware of any of the previous ones and each request is executed independently. Given its stateless nature, simple mechanisms such as HTTP cookies were created to overcome the issue.

An HTTP cookie (also called web cookie, Internet cookie, browser cookie, or simply cookie) is a small piece of data sent from a website and stored on the user's computer by the user's web browser while the user is browsing. Cookies were designed to be a reliable mechanism for websites to remember stateful information (such as items added in the shopping cart in an online store) or to record the user's browsing activity (including clicking particular buttons, logging in, or recording which pages were visited in the past). They can also be used to remember pieces of information that the user previously entered into form fields, such as names, addresses, passwords, and credit card numbers.

They are like ID cards for websites. If a browser sends a certain cookie to a web server, the server deduces the identity of said client from that cookie, without requiring authentication. This can pose problems from a security perspective. For more details, check the section about cookie theft and session hijacking.

What are Cookies?

A cookie is a key-value pair stored in a text file on the user’s computer. This file can be found, for example, at the following path on a Linux system using Firefox:

~/.mozilla/firefox/<some_random_characters>.default-release/cookies.sqlite

As the file name implies, Firefox stores cookies in an SQLite database.

An example of cookies set for a website could be:

username=admincookie_consent=1theme=dark

The first cookie stores the username, so it can be displayed to the user without querying the database. The second one stores the choice made by the user regarding their concent to receive cookies, so the application does not continue to show that annoying message every time. Finally, the third one stores which theme was selected (in this case, a dark theme).

Once a cookie has been set, the browser will send the cookie information in all subsequent HTTP requests until the cookie is deleted. Cookies also have various attributes:

DomainandPath: define the scope of the cookies. These attributes tell the browser what website they belong to.Secure: defines that cookies should only be sent using secure channels such as HTTPS.Expires: specifies when the cookie is to be deleted. All cookies have a maximum lifespan, after which they must be erased by the browser, for security. That why if you haven't logged on a website for a long time, you will be logged out.- Alternatively, the`Max-Age` attribute can be used to state the number of seconds after the cookie is to be deleted.

Developer Tools

All modern browsers have the ability to assist developers in creating, previewing, testing and debugging their web applications.

This ability comes in the form of the Developer Tools suite.

You can open the Developer Tools by pressing either F12 or Ctrl + Shift + c when browsing through a website.

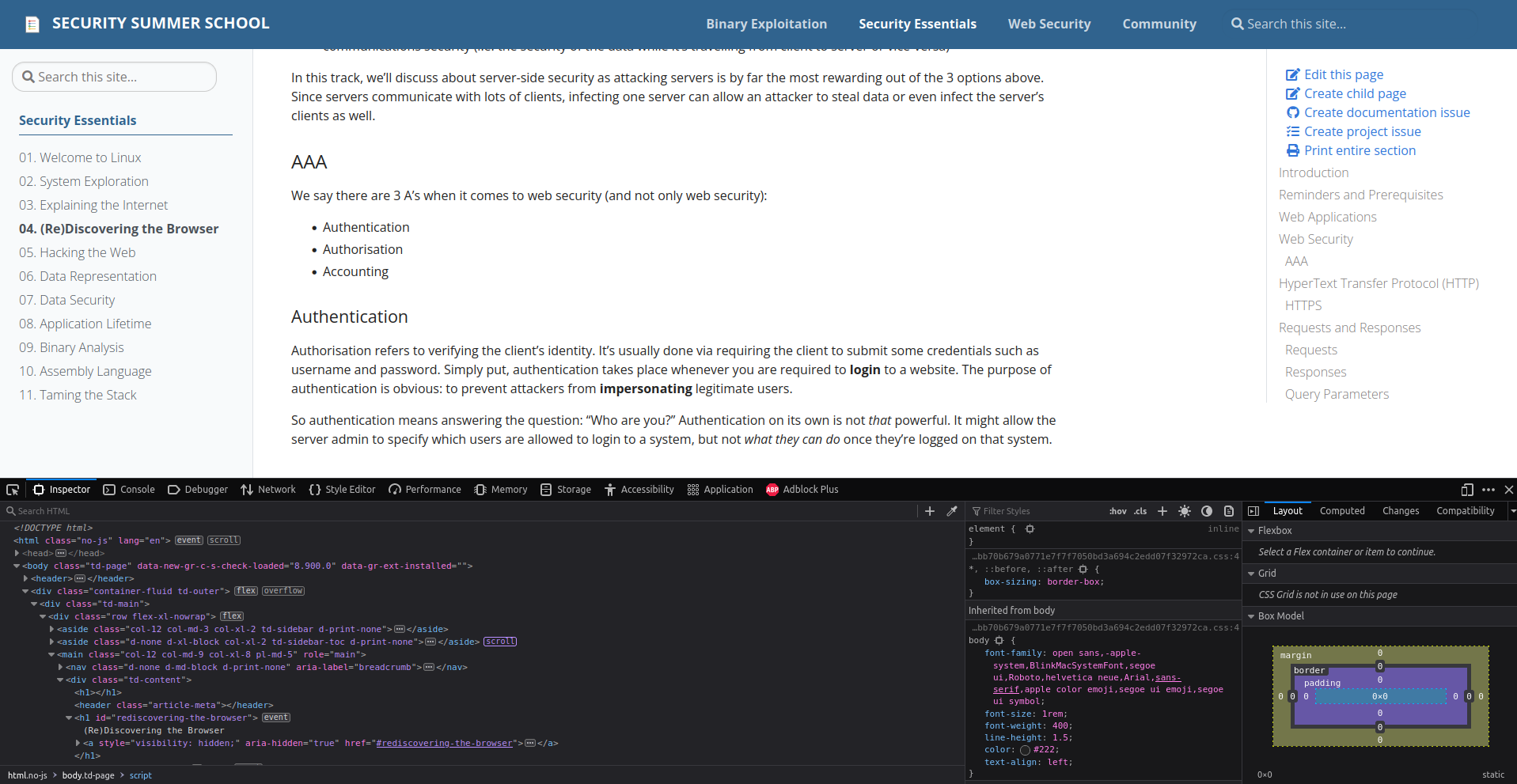

Inspector

The first "tab" we see in the Developer Tools is called Inspector. It displays the HTML source of the page we are viewing. This structure is called the Document Object Model. We can even modify the content of the HTML document

Of course, this modification is only visible to me because I'm modifying my local copy of the index.html file.

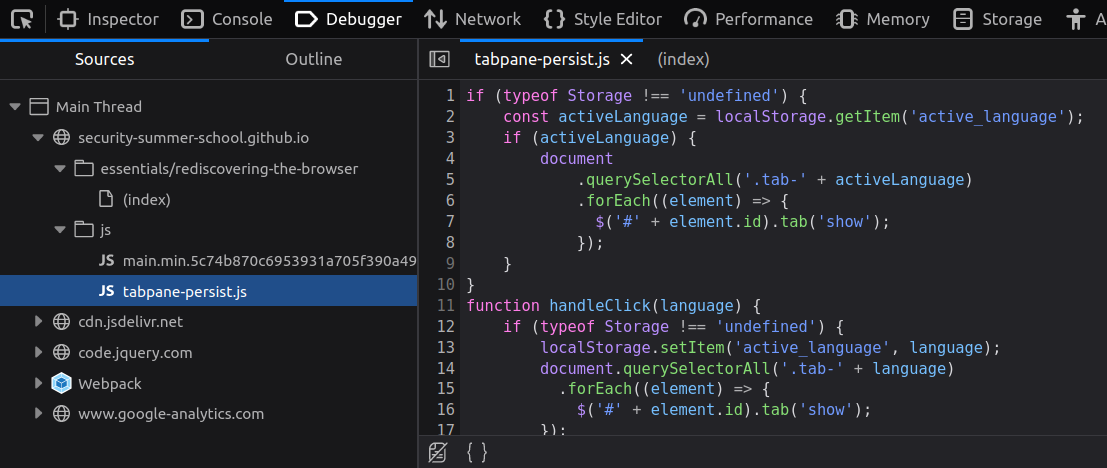

Console

This tab is pretty straightforward. It is a shell in which we can write JavaScript code.

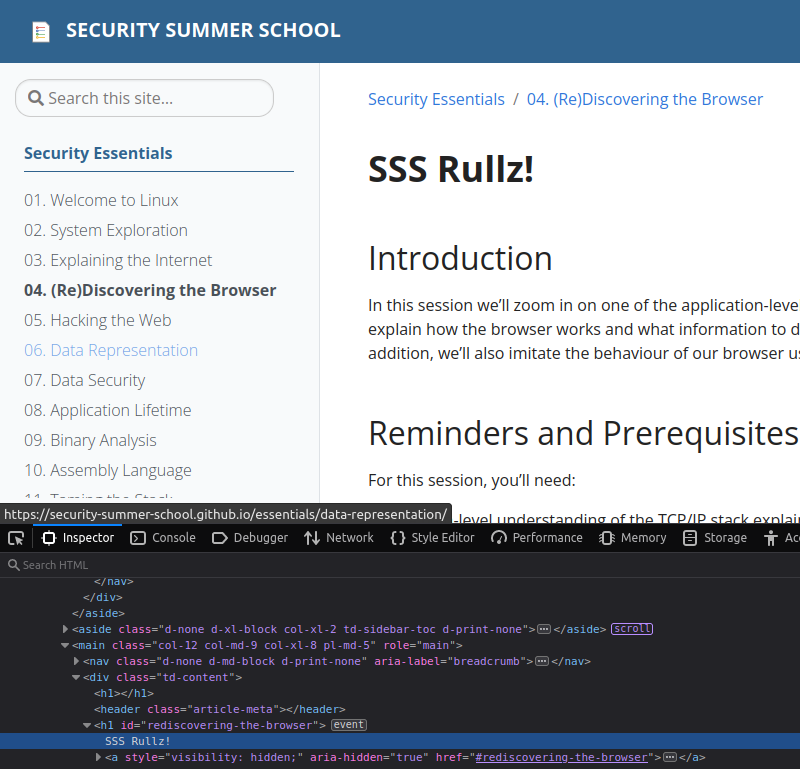

Debugger

This tab displays all the files loaded by the web page and allows you to run the JavaScript code step by step. Hence its name: Debugger

Sources

The "Sources" sub-tab of the "Debugger" tab shows the hierarchical structure of all files used by the web page. These files can be HTML files, CSS files images, videos, JavaScript files, anything.

Notice the file (index) is actually the same we saw in Inspector.

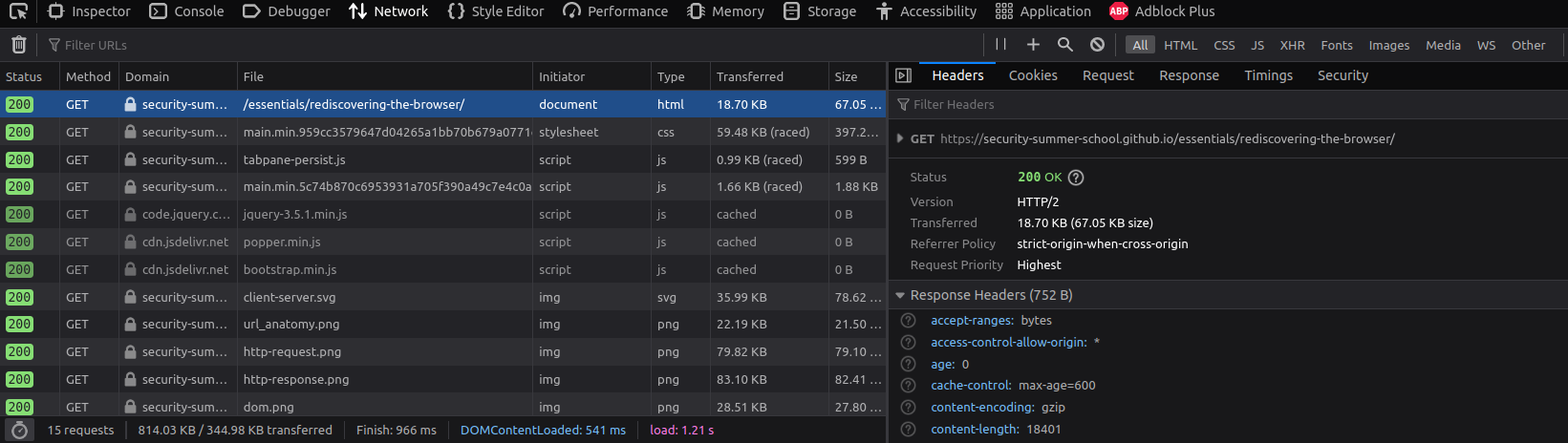

Network

The network tab shows detailed information about every file loaded and every request and response made by the page.

Notice the sub-tabs to the right.

here you can find in-depth information about the HTTP requests, such as HTTP parameters, HTTP methods (GET, POST etc.), HTTP status codes (200, 404, 500, etc.), loading time and size of each loaded element (image, script, etc).

Furthermore, clicking on one of the requests there, you can see the headers, the preview, the response (as raw content) and others.

This is useful for listing all the resources needed by a page, such as if there are any requests to APIs, additional scripts loaded, etc.

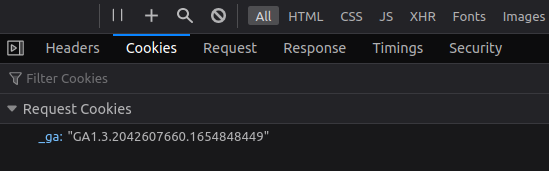

Here we can also see the cookies sent with each request.

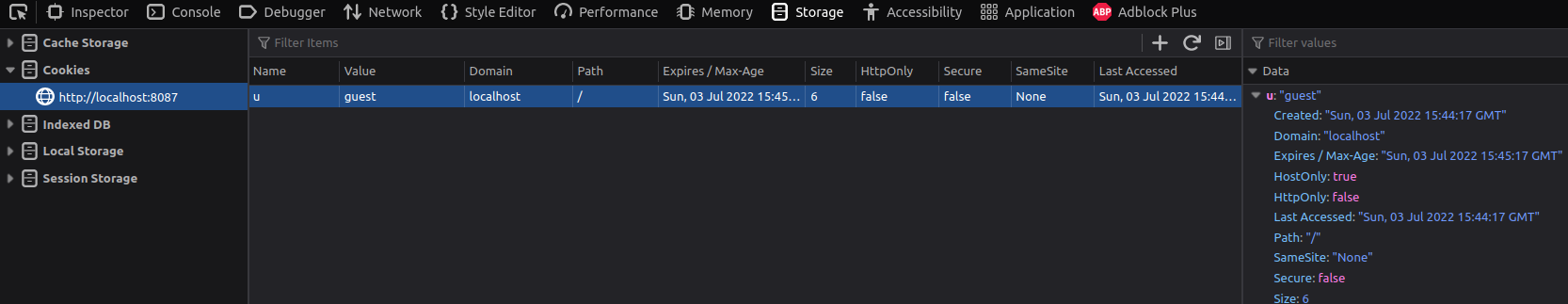

Storage

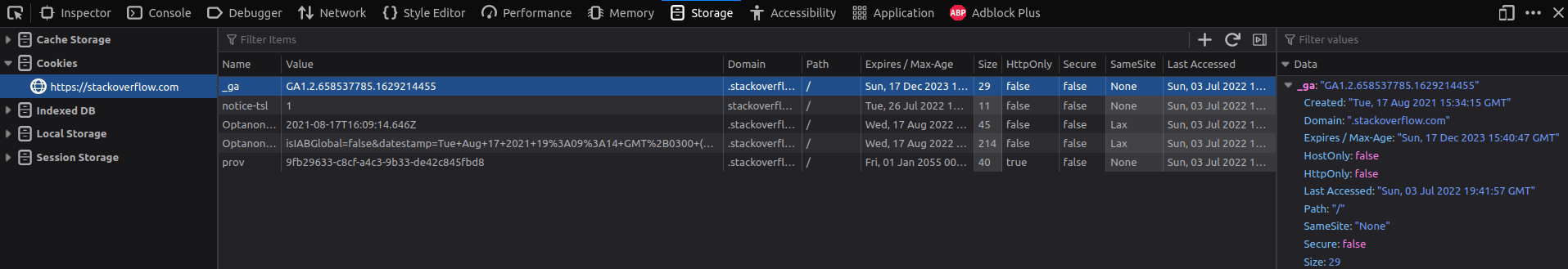

Viewing cookies in the "Network" tab is fine, but that only gives us their value. If we want to see all their attributes and change their value, we need to go over to the "Storage" tab.

Let's take a closer look at one cookie called _ga.

It comes form "Google Analytics".

This is a service provided by Google that definitely does not spy on users, but it uses cookies like this one to give website owners statistics about their visitors.

So it's literally spying and tracking users' behaviour.

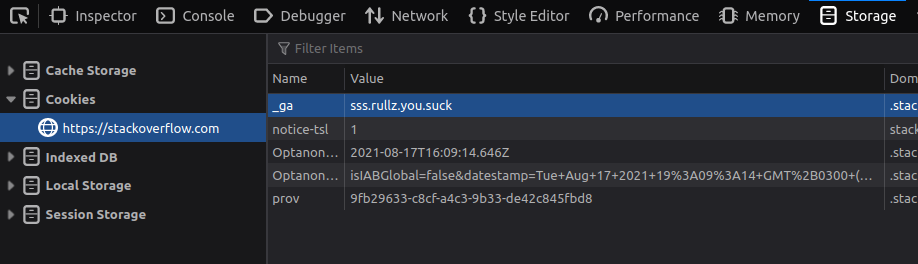

Let's troll them by modifying their cookie Its contents are explained here. But we're just going to mess with it.

There! We showed Big Tech not to mess with us!

Cookies from the CLI

We're going to use our old friend curl.

To set a cookie we simply use the -b parameter like so:

root@kali:~# curl -b 'something=nothing' -b 'something_else=still_nothing' $URL

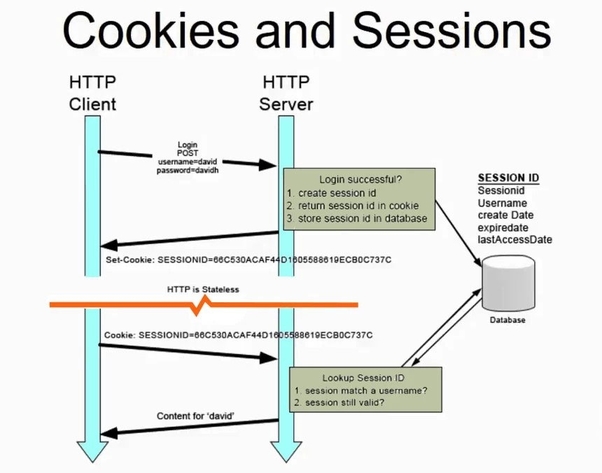

HTTP Sessions

Some websites use sessions to remember their clients across multiple requests.

These sessions are essentially IDs with which the server identifies clients.

For example, PHP uses a cookie called PHPSESSID.

It contains a random large number.

Sessions are usually short-lived, which makes them ideal for storing temporary states between pages. Sessions also expire once the user closes his browser or after a predefined amount of time (for example, 30 minutes).

The basic workflow is:

- The server starts a new session (sets a cookie via the HTTP

Cookieheader). - The server sets a new session variable (stored on the server-side).

- When the client changes the page, it sends all the cookies in the request, along with the session ID from step 1.

- The server reads the session ID from the cookie.

- The server matches the session ID with the entries of a local list (in-memory, text file etc.).

- If the server finds a match, it reads the stored variables.

For PHP, these variables will become available in the superglobal variable

$_SESSION. - If the server doesn't find a match, it will create a new session and repeat steps 1-6.

Example of a session in PHP (running on the server):

<?php

session_start(); // Start the session

$_SESSION['username'] = "John Doe";

$_SESSION['is_admin'] = true;

echo "Hello " . $_SESSION['username'];

?>

Sessions in the CLI

Guess who's back?

curl, of course.

We can save the cookies sent by a server in a cookie jar.

Remember this concept.

Python uses it too.

It's not too sophisticated, either.

A cookie jar is a file that contains cookies.

To save the cookies in a file, we use the -c <file name> option

root@kali:~# curl -c cookies.txt $URL

[...]

root@kali:~# cat cookies.txt

# Netscape HTTP Cookie File

# https://curl.haxx.se/docs/http-cookies.html

# This file was generated by libcurl! Edit at your own risk.

sample.domain.com FALSE / FALSE 1656864260 something nothing

Each entry in a cookies file represents a cookie. Its layout is:

<domain> <include subdomains> <path> <HTTPS only> <expires at> <cookie name> <cookie value>

We are free to modify this cookies file however we want.

As you can see, this file has a very specific format.

It's better to let curl generate it first to make sure it's correct and only then edit it ourselves.

Then, in order to use these cookies in a subsequent request, we use the -b parameter:

root@kali:~# curl -b cookies.txt $URL

Notice it's the same parameter we used to send cookies manually.

When the argument is a file, curl reads the cookies form the file.

Otherwise, it reads them from the argument itself as strings.

Sessions in Python

In order to send HTTP requests in Python, we can import the requests module.

Then, we simply create a session object which we then use to send requests.

This object also maintains the session cookies.

They are accessible via session.cookies.

s = requests.Session()

# Set the value of the `something` cookie to `nothing`.

s.cookies.set('something', 'nothing')

# Send a `GET` request with the above cookie.

s.get($URL)

Path Traversal

Every request asks for a file.

Remember GET /path/to/file.

Even GET / implicitly asks for index.html or index.php.

If the application does not verify the parameter, an attacker might be able to exploit the application and display an arbitrary file from the target system. Normally an attacker would try to access sensitive files containing passwords or configurations in order to gain access to the system. Remember that PHP scripts aren't normally visible by the client.

Below is an example of a vulnerability where an attacker can leak PHP scripts: Consider the following URL:

http://somesite.com/view.php?file=image.jpg

What if the attacker could query the website using view.php as parameter?

http://somesite.com/view.php?file=view.php

This would be too easy. Sometimes, images are stored in different directories than application files. So our attacker should query the server like with a link like this one:

http://somesite.com/view.php?file=../../view.php

If they manage to view view.php, then it is likely they can access any file on the system, such as /etc/passwd, using this query:

http://somesite.com/view.php?file=/etc/passwd

This kind of situation when an attacker can freely access files on the server is called a path traversal attack. To fix this, applications should always validate user input and ensure the path they request is within a safe folder to which they have access.

DIRectory Buster (DIRB)

There may be other files stored on the server that aren't accessible from the entry point web page.

It is difficult to search for such pages manually.

Luckily there are tools that can help us with this.

One of them is DIRectory Buster, or dirb in short.

It simply queries a web server for many files fast.

All you need to do is to give it a list of files for which to search.

Here's how to run it:

root@kali:~# dirb <URL> wordlist.txt

A good starting point for wordlists are the lists here, particularly those named raft-large-*.txt:

raft-large-files.txtfor files, duh...raft-large-directories.txtfor directories

dirb works by issuing lots of GET requests, one for each file in its wordlist.

If a request receives a 404 response, the file doesn't exist.

Otherwise, it does (except for 500 responses, in which case the request is resent).

Even a 403 response is alright.

It just means that a regular user doesn't have access to that file.

Here's what dirb + SecLists look like:

root@kali:~# dirb http://example.com ~/SecLists/Discovery/Web-Content/raft-large-files.txt

[...]

---- Scanning URL: http://example.com/ ----

+ http://example.com/index.html (CODE:200|SIZE:1256)

+ http://example.com/. (CODE:200|SIZE:1256)

+ http://example.com/extension.inc (CODE:403|SIZE:345)

[...]

Summary

The key takeaways from this session are:

- HTTP cookies are used to make the protocol stateful.

You can pass them with

curlby using the-bparameter - Sessions are cookies used to identify a client.

Both

curland Python can account for sessions:- `curl` does so by saving and loading them from a cookie file with the `-c` and `-c` parameters, respectively

- Python uses a `Session` object that stores cookies internally - In path traversal attacks hackers can access files they shouldn't be allowed to by specifying the path to them

- A very useful tool for testing the existence of additional files is

dirb.

- A very useful tool for testing the existence of additional files is

- One of the most widely used repositories of lists of common names / passwords / anything is SecLists. Use it any time.

Activities

Tutorial - Chef Hacky McHack

We'll solve this task in 3 ways: from the browser, from the CLI and using Python. That good we are!

Virgin: From the Browser

We visit to the URL, open the Developer Tools and go over to the "Storage" tab.

There we see the server has given ass the cookie u=guest.

Since the challenge is called "Hacky McHack" we set the cookie value to hacky mchack.

We notice a new tab has appeared at the top of the page or by inspecting the HTML source: Manage (/manage.php).

We click on it and get the flag.

<ul class="nav-menu list-unstyled">

<li><a href="index.php" class="smoothScroll">Home</a></li>

<li><a href="#about" class="smoothScroll">About</a></li>

<li><a href="#portfolio" class="smoothScroll">Portfolio</a></li>

<li><a href="#journal" class="smoothScroll">Blog</a></li>

<li><a href="#contact" class="smoothScroll">Contact</a></li>

<li><a href="manage.php" class="smoothScroll">Manage</a></li>

</ul>

Chad v1: From the CLI

We use our good friend curl.

First, we save the cookies from the initial page into a cookie jar.

root@kali:~# curl -c cookies.txt http://141.85.224.70:8010

[...]

root@kali:~# cat cookies.txt

# Netscape HTTP Cookie File

# https://curl.haxx.se/docs/http-cookies.html

# This file was generated by libcurl! Edit at your own risk.

http://141.85.224.70:8010 FALSE / FALSE 1656864260 u guest

Now we edit the file and replace guest with hacky mchack and send a GET request to /manage.php.

root@kali:~# sed -i s/guest/hacky\ mchack/ cookies.txt

root@kali:~# curl -b cookies.txt $URL/manage.php

If we didn't want to use the cookie jar, we could have simply looked at the headers sent by the server then sent the cookie "manually":

root@kali:~# curl -v $URL > /dev/null # we don't care about the output

[...]

< HTTP/1.1 200 OK

< Date: Sun, 03 Jul 2022 16:10:51 GMT

< Server: Apache/2.4.38 (Debian)

< X-Powered-By: PHP/7.2.34

< Set-Cookie: u=guest; expires=Sun, 03-Jul-2022 16:11:51 GMT; Max-Age=60

root@kali:~# curl -b 'u=hacky mchack' $URL/manage.php # Notice the Set-Cookie field above

<here we get the flag>

Chad v2: From Python

Simply create a Session object, set the cookie u to hacky mchack, then send a GET request to the /manage.php endpoint.

Challenge: Beep Beep Boop

Look for hidden files on the web server.

Challenge: Colours

Indices go brrrrrrr.

Challenge: Great Names

Do you know these great explorers?

Challenge: Nobody Loves Me

Whom do you call?

Challenge: One-by-One

One by one by one by one by one...

Challenge: Produce-Consume

What does the server produce exactly?

Challenge: Traverse the Universe

Explore new ~planets~ files.

Further Reading

Cookie Theft / Session Hijacking

Enter Facebook then close the tab. Next time you won't be asked to login. This is because Facebook has given you a session ID with which you no longer need to log in. It would be a pity if an attacker stole your ID. This is what's called cookie theft or session Hijacking.

It's a pretty common attack that mostly requires the user to click on a malicious link that leads to a webpage whose JavaScript code reads the victim's cookies. Following this attack, hackers can impersonate you wherever you were logged in.

Here are more ways in which your session can be stolen.