URLs

In the above ping command, we used google.com instead of an IP.

But what exactly are strings such as https://www.youtube.com or https://www.google.com?

Uniform Resource Locators (URLs) are exactly what their name implies: addresses to given resources on the Web. This means that each URL can point to at most one resource (some URLs are invalid and, thus, point to no resources). Such resources can be HTML pages, images, videos and many others.

Here are some examples of URLs:

https://security-summer-school.github.iohttps://github.com/security-summer-school/essentials/blob/master/explaining-the-internet/README.mdhttps://www.google.com/search?q=security+summer+school

You've probably figured out that these URLs look somewhat similar.

They all start with https://, they look like paths in the file system, separated by /, they use some special characters such as ? and +.

In the next section, we'll explain all of these components.

Anatomy of a URL

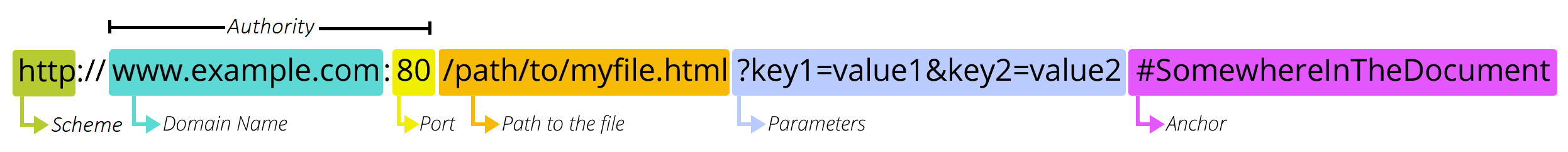

The image below summarises the building blocks of a URL

Let's dissect these components:

- The scheme (sometimes called schema) indicates the application layer protocol that the browser must use to request the resource.

Usually, for websites, the protocol is HTTP (unsecured) or HTTPS (secured).

We'll get into the details of HTTP in the next session.

Other schemes include

ftp(File Transfer Protocol),git,mailtoetc. - The authority is separated from the scheme by the characters

://It includes both the domain (in our case:www.example.com) and the port (80), separated by a colon:- The domain indicates which Web server is being requested. Usually this is a domain name, but an IP address may also be used (as you've seen when solving our challenges).

- The port indicates the technical gate used to access the resources on the web server. It is usually omitted if the web server uses the standard ports of the HTTP protocol (80 for HTTP and 443 for HTTPS) to grant access to its resources. We'll explain this concept in further detail in the Transport Layer section.

- The path to the resource was, in the early days of the internet, a physical file location on the web server. Nowadays, it is mostly an abstraction handled by web servers without any mandatory physical reality.

- The parameters are like function parameters, but they are passed to the web server itself.

Those parameters are a list of key - value pairs separated with the

&symbol. The web server can use those parameters to do extra stuff before returning the resource. Each web server has its own rules regarding parameters. Once again, we'll learn more about these parameters, more commonly known as query parameters in the next session. - The anchor, also known as fragment, is like a bookmark to some specific part of the resource. It gives the browser directions to show the content located at that bookmarked spot. On an HTML document, for example, the browser will scroll to the point where the anchor is defined, but on a video or audio document, the browser will try to go to the time the anchor represents. Markdown documents also use anchors, like so: https://github.com/security-summer-school/essentials/tree/master/explaining-the-internet#anatomy-of-a-url.

You might have heard the same things being called Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs). This is correct, but it's not the most precise name you can use. In order to understand the difference between URLs and URIs, check out their corresponding section.

We'll see how URLs are translated into IPs by a naming system called the Domain Name System (DNS).