Browsers

Browsers are the most common type of client for web servers. They send requests to servers like the ones we outlined before. Servers respond with text files, images, audio files, all kinds of data. Browsers also store those precious cookies that all websites are eager to give you. We'll dive deeper into browsers next session.

For now, press Ctrl + u in your browser.

It should lead you to a more weird-looking version of our website.

This is the HTML code that the browser renders in order to display its contents in a more "eye-candy" fashion (insert images, code snippets, videos etc.).

HTML

As we've already established, HTML stands for HyperText Markup Language.

It's a description language, in which the text content of a website is stored.

If you look at view-source:https://security-summer-school.github.io/essentials/rediscovering-the-browser/, you'll find that the sentences in the .html file are the same as those on GitHub.

security-summer-school.github.io is built using Docsy.

Among many other things, Docsy can convert Markdown files to HTML.

This is how we write these sessions in Markdown (another markup language), but you see them in HTML.

The Document Object Model (DOM)

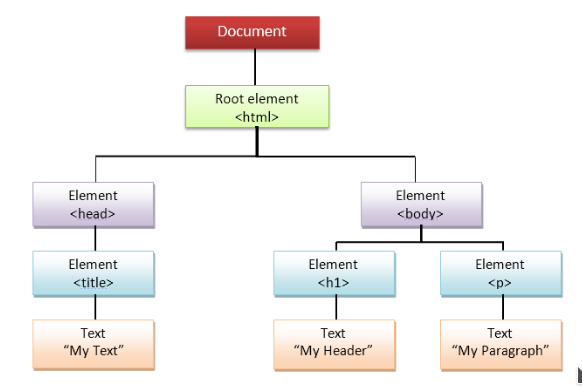

Every HTML file is organised hierarchically by what's called a Document Object Model (DOM). It connects web pages to scripts or programming languages by representing the structure of a document, such as the HTML representing a web page, in memory.

The DOM represents a document as a tree data structure. Each branch of the tree ends in a node, and each node contains objects. DOM methods allow programmatic access to the tree. With them, you can change the document's structure, style, or content.

Every element within your document is an object: \<head\> or \<body\> tags etc.

DOMs are flexible and allow easy introduction of nodes, as all objects are nodes.

The DOM can also be used to make changes to the contents of the HTML document, such as creating animations or validating input etc.

DOMs are outside the scope of the Security Essentials track. To get a better understanding of DOMs, join the Web Security track next year.

"Browsers" From the CLI

The browser is all nice and good-looking, but is not so easily configurable. It's a bit difficult to add your own headers to a request form a browser, for example. And good luck writing a script that launches subsequent, interdependent browser requests. When it comes to hacking and crafting very specific HTTP requests, we need to move away from the browser and into the CLI.

curl

The most versatile command-line tool for creating and sending HTTP requests is by far curl.

It's syntax is at firs really simple:

root@kali:~# curl <URL>

To see the full request and response, use the -v parameter:

root@kali:~# curl -v example.com

* Trying 93.184.216.34:80...

* TCP_NODELAY set

* Connected to example.com (93.184.216.34) port 80 (#0)

> GET / HTTP/1.1

> Host: example.com

> User-Agent: curl/7.68.0

> Accept: */*

>

* Mark bundle as not supporting multiuse

< HTTP/1.1 200 OK

< Age: 441067

< Cache-Control: max-age=604800

< Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

< Date: Sat, 02 Jul 2022 18:33:49 GMT

< Etag: "3147526947+ident"

< Expires: Sat, 09 Jul 2022 18:33:49 GMT

< Last-Modified: Thu, 17 Oct 2019 07:18:26 GMT

< Server: ECS (dcb/7EEA)

< Vary: Accept-Encoding

< X-Cache: HIT

< Content-Length: 1256

<

<!doctype html>

[...]

The request is very simple:

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

User-Agent: curl/7.68.0

Accept: */*

It requests the root of the website, that the client (User-Agent) is curl version 7.68.0, and that it accepts any type of response (Accept).

The server at example.com answers with the code 200, meaning the request was handled smoothly.

It specifies that the delivered content is an HTML file (Content-Type: text/html), with UTF-8 encoding (charset=UTF-8).

If you don't know what UTF-8 is yet, it's a convention on how to encode characters.

We will explain it along with other encodings in session Data Representation.

Notice that since the response does contain a body (i. e. the HTML contents of example.com), the Content-Length field is also present and set to the size of the HTML file.

curl's versatility comes from the fact that we can enrich this request by specifying query parameters and even a body.

URL encodings

Head over to your browser and search for security; summer ? school.

Take a look at the link in the browser:

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-lm&q=security%3B+summer+%3F+school

To recap, its query parameters are:

client=firefox-b-lmq=security%3B+summer+%3F+school

The first parameter seems reasonable.

But what's with the weird symbols in the value of q?

Those symbols are the URL encodings of ; and ?.

In order for the value of q not to contain some specific characters used by URLs (such as ? to separate the path from the query parameters), those characters are encoded differently in the URL.

It's something similar to escaping characters in bash.

Specifically, in the URL below:

+is the URL encoding for space%3Bis the URL encoding for;%3Fis the URL encoding for?

wget

Do not confuse it with curl!

Its man page clearly states:

wget- The non-interactive network downloader.

In other words, while curl is an HTTP client which, obviously, receives HTTP responses, wget is used for downloading files and nothing else.

Let's try it out:

root@kali:~# wget example.com

[...]

index.html 100%[===================>] 1,23K --.-KB/s in 0s

root@kali:~# cat index.html # Now we have the file locally.

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Example Domain</title>

[...]