HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP)

As its name implies, HTTP was initially used to transfer text-based data, because when it was proposed in 1991, that's what its creators imagined the internet was going to be: a collection of text files. Later versions of HTTP started to accommodate more types of data, including video, audio and even raw bytes. Nowadays, you can send anything via HTTP. Still, one of the main things that browsers receive via HTTP is HTML (HyperText Markup Language). We'll dive into HTML a bit later in this session.

Notice that both HTTP and HTML contain the word "HyperText". It refers to a property of websites to contain references to other websites or to other parts of the same website, thus creating a web-like structure of the internet, thus the World-Wide Web. Markdown is another hypertext language. We use Markdown to write text content for the Security Summer School. We can use references to other sections of the same document, or to other websites entirely.

As you may remember from the previous session, HTTP is an application-layer protocol. This means it sits at the top of the TCP/IP stack and mostly receives and sends user data from and to its underlying transport protocol. As the transferred data is mostly text, error checking is important. Thus, the transport-layer protocol used by HTTP is TCP.

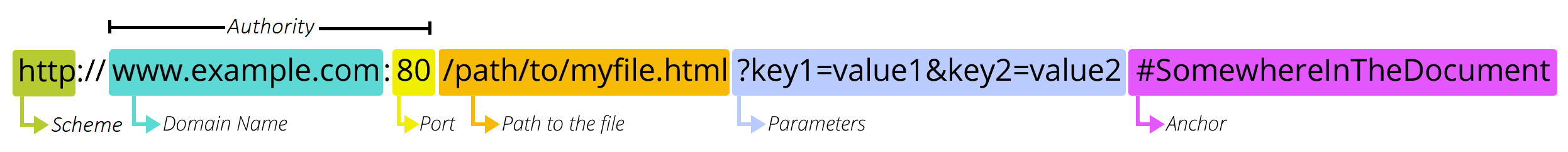

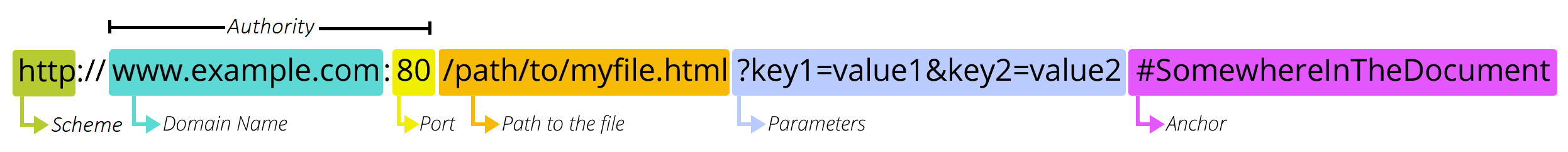

Most websites nowadays use HTTP or HTTPS to transfer data. Remember the anatomy of a URL, also from the previous session.

The first part of a URL is called the scheme.

It defines the protocol used for interacting with that website.

In the example above, the scheme is http, i.e. messages to and from the website www.example.com will be passed using HTTP.

By default, HTTP uses port 80 to listen for connections, but we can use any other port we want.

Usually, these ports are in the 8000 - 8099 range to maintain some visual consistency with the original port.

The http scheme isn't so common now.

Most websites you visit on a daily basis use a different scheme: https.

security-summer-school.github.io, for example, uses HTTPS.

HTTPS

HTTPS stands for HTTP Secure. As we're going to see in the next section, HTTP sends data in clear text. This means that any attacker can intercept network traffic and see what data is being transferred. HTTPS was developed to remedy this vulnerability. Instead of being built on top of TCP, HTTPS is built on top of yet another application-level-protocol: Transport Layer Security (TLS). TLS allows data sent via HTTPS to be encrypted, thus making it unintelligible for attackers.

Requests and Responses

HTTP has 4 properties that have allowed it to become ubiquitous in the internet:

Statelessness: by default HTTP is a simple request-response protocol maintaining no state between successive communications. Its design specifies that every request is independent from any other. This is good for designing a web server as it makes it simpler and cleaner, but what if that server is Facebook? Once you log in, you want it to "remember" who you are so you can still be logged in after more than 1 click. A stateless protocol cannot do this. This shortcoming has led to the design of cookies, which are small pieces of information exchanged between the client and the web application. They are used to "remind" the server who the client is upon each request. We'll discuss cookies in the next session.

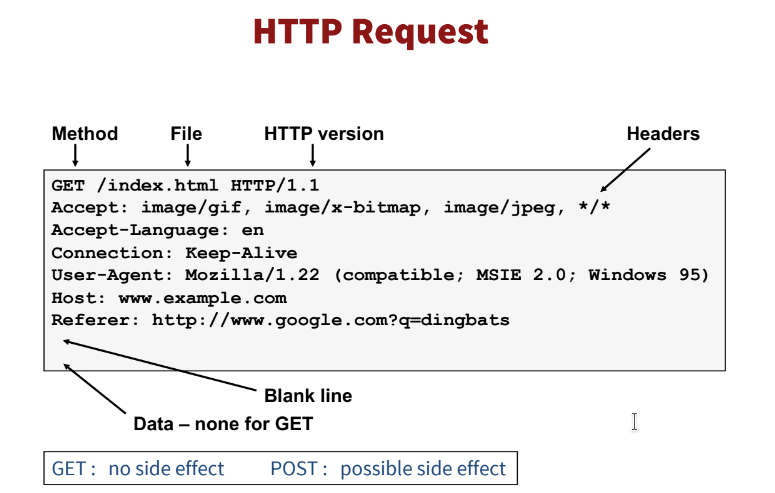

Message format: HTTP requests have a specific format. Namely, they are comprised of plain-text header and data (although newer improvements also implement a binary protocol). The header contains various information about the client or the server (e.g. a user-agent, page caching information, text encoding information), while the payload is very often (but not always) an HTML page.

Addressing: resources on the web are located using the URL addressing scheme. Possible vulnerabilities here include a misconfigured web server that allows viewing application-specific files, or worse, that allows accessing other files on the host machine. While this information leakage is not very dangerous by itself, it may be used as an intermediary stage for other attacks. You can read more about URLs here.

Request methods: HTTP communication is done by using methods, also called HTTP verbs. The most used methods are

GET,POST,PUTandDELETE.- The `GET` method is read-only and is used to retrieve data from the server.

- A `DELETE` request is used to remove the specified resource from the server.

- The `PUT` method is used to modify an entire resource.

- `POST` requests are used to create new resources.

You can find more information about all existing methods here.

Communication between a client and a server usually follows these steps:

- A client (a browser) sends an HTTP request to the web.

- A web server receives the request.

- The server runs an application to process the request.

- The server returns an HTTP response (output) to the browser.

- The client (the browser) receives the response.

Requests

Here we have a GET request.

It is made for a file: /index.html.

Remember the path from the anatomy of a URL:

This is the file that you request.

The path is like a path in the Linux file system.

In the image above, the request asks for the file /path/to/myfile.html.

So the request would look something like:

GET /path/to/myfile.html HTTP/1.1

[...]

Below the first line in the picture that precedes the anatomy of a URL, we can find the headers of the request. They are metadata used to provide additional information about the connection, about the client and about how to handle the request. Some usual headers are:

- Host: indicates the desired host handling the request

- Accept: indicates what MIME type(s) are accepted by the client; often used to specify JSON or XML output for web-services

- Cookie: passes cookie data to the server

- Referrer: page leading to this request (note: this is not passed to other servers when using HTTPS on the origin)

- Authorization: used for basic auth pages (mainly).

It takes the form "Basic <username:password encoded with base64 >"

Don't worry about what

base64is now. We'll explain it in the Data Representation session. Content-Type: specifies the format of the data Some examples are:text/htmlfor a HTML pagetext/plainfor plain textapplication/jsonfor JSON filesimage/jpegfor JPEG images

- Content-Length: specifies the size in bytes of the body. The body is the data that comes along with a request or response. It is described in some more detail in its own section.

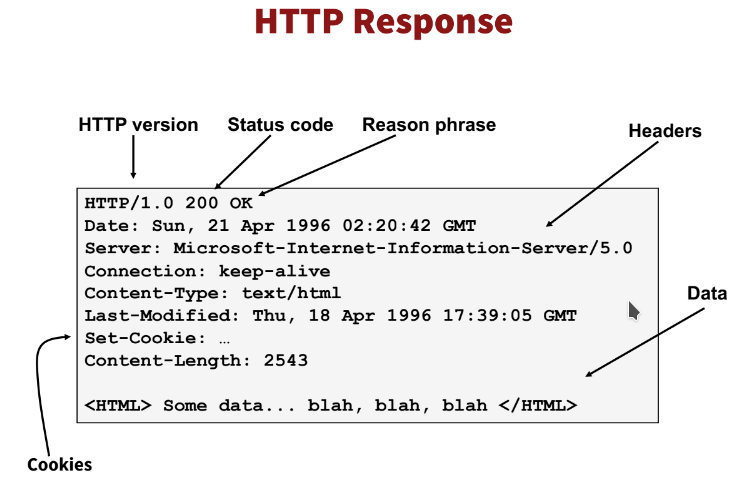

Responses

1xx: informational responses2xx: the request was fulfilled successfully. The most common code is200.3xx: redirects - the request was passed to another server4xx: client errors. Some very common client errors are:400: bad request - there's an error in the request.404: not found - the requested resource doesn't exist. For example, in case/file.txtdoesn't exist and the client sendsGET /file.txt HTTP/1.1, the server answers with404.403: unauthorised - you don't have access to that resource. Let's say the filesecret.txtexists, but is only accessible to theadminuser. If a regular user sendsGET /secret.txt HTTP/1.1, they would get a403response in return.405: method not allowed - say a server only allowsGETandPOSTmethods. You would get a405response if you sent it aPUTmethod, for example.

5xx: server errors

Query Parameters

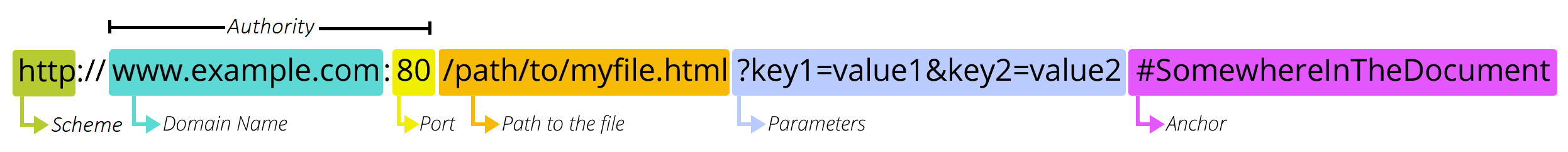

This is the last time today that you'll se the image with the anatomy of a URL, we promise.

Look at the parameters of the URL

They are highlighted in blue.

Query parameters are key-value pairs that the server can retrieve from the request.

So in our example, the server can see that key1 has the value value1 and value2 corresponds to key2.

Think of HTTP queries/requests (GET, POST, PUT etc.) as functions.

They return something (the codes explained in the earlier section and sometimes data, like in the case of GET) and might have side effects (POST, PUT, DELETE come to mind here).

Each pair of path and method is equivalent to a function.

In any programming language, functions also take arguments.

These arguments are the query parameters of a request.

And just like function arguments, they provide input to the server, values by which the client can alter its behaviour.

Request Body

Obviously, HTTP requests may also contain raw data.

For example, if we use a POST method, we also have to provide the data to be saved on the server.

Notice that the field Content-Length from the header of the request must contain the length of the body.

Otherwise, the server may discard any bytes that exceed the specified Content-Length.